Visiting OpenAI: Reflections from a Philosopher’s Desk

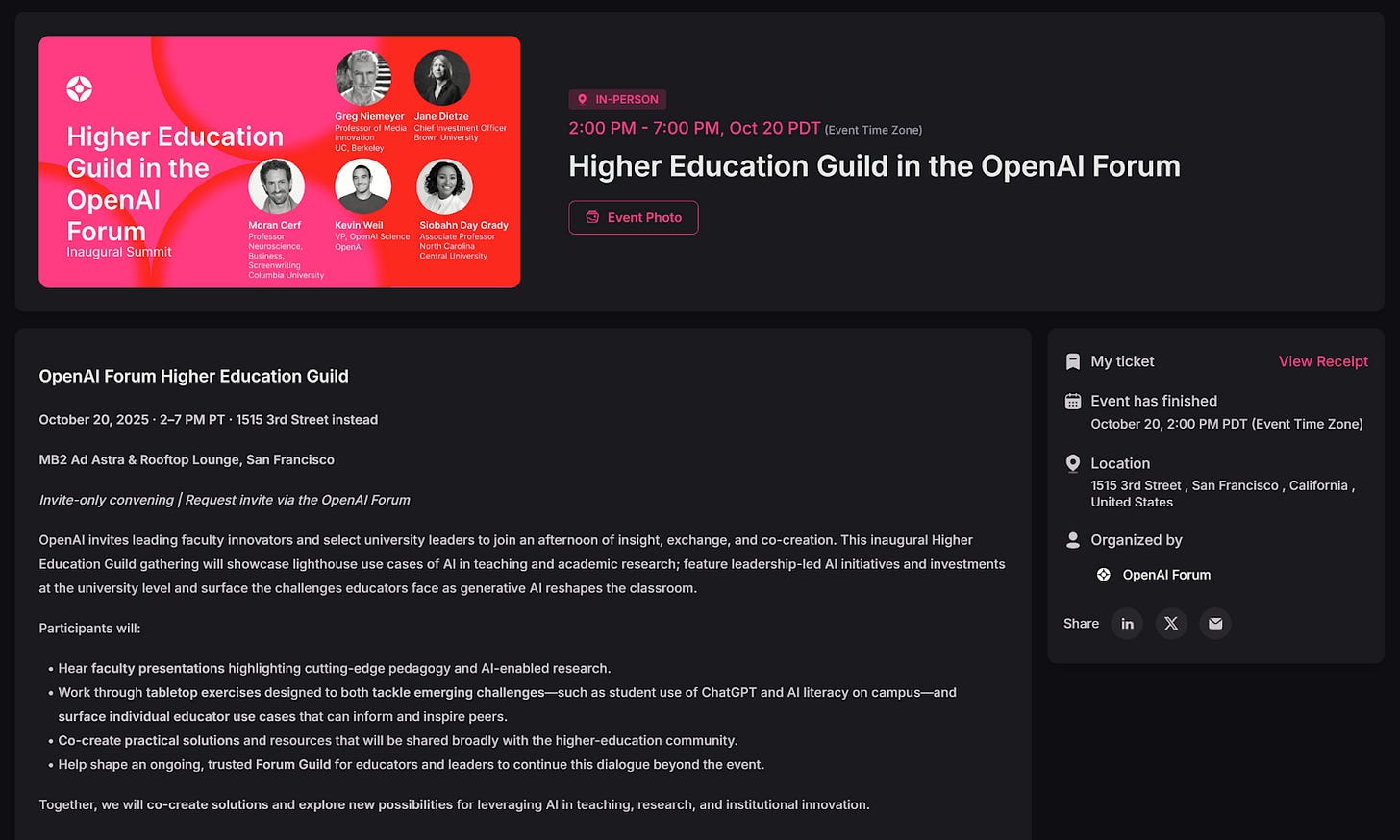

In which the author attends the inaugural summit of the "Higher Education Guild" at OpenAI's headquarters...

I arrive in San Francisco early and wander along the water, feeling like an inefficient thinking machine.

I have to pee. I fret about texts. I eat an egg. I experience an erotic thought. I wish for touch. I chew my lip. I feel alone. I take propranolol.

I need to find Troy Fenwick.* I don’t know Troy. Really, I’ve hardly heard of him. But Troy’s a philosopher, and he’s coming, too. In my mind, Troy is the real deal. In my mind, Troy is meditating on the Singularity, the instrumentalization of learning, the pedagogical importance of lived experience. He is writing hinged things. He is returning his referee reports in a timely manner. I intend to find Troy Fenwick.

I watch the machines on the water moving senselessly this way and that. I wonder whether Troy is nice. I think about my playful P.O. box. I pick detritus off my shirt. I take a selfie. I examine the selfie. I delete the selfie.

My ankles ache. They are defective.

The first-person narration is compellingly neurotic, but it risks over-identification. You might want to increase the reflective distance slightly—not by becoming more abstract, but by introducing more tonal layering. Occasional self-awareness (“I know I am performing a caricature of the anxious academic”) would sharpen rather than blunt the vulnerability.

The security guard takes my California license and, finding my name, ushers me into the moneyed foyer. Everything is supple and inviting. My badge sits on a table next to huge silicone mushrooms emanating whimsical blue light. I am directed to sign a Safety Acknowledgement (stay with your host for your safety!) and an NDA by a cheerfully attentive employee. He is young, slim, and attractive. I finish, and a swag bag appears. I am ushered into the well-appointed room.

Beleaguered academics chat while resting on designer furniture. I pour a cup of decaf in order to have something to do with my hands and mouth. I send a text message, bragging feebly about my swag bag. I don’t think I see Troy, but, also, I don’t know what Troy looks like. There’s an opening on a rug next to a group of scientists.

“Do y’all mind if I awkwardly sit here?”

“Go ahead.” An avuncular man smiles and welcomes me.

Now that I’m sitting down, I arrange my face. We are talking about brain drain in Texas. Then we are saying The Things about AI in education: It’s the floor, not the ceiling; blue books have their place; students can dialogue with it; Graham Burnett; have you tried oral exams; it can be a useful writing tool. I voice my opinion that in philosophical pedagogy, the writing process is more important than the product. The scientists nod politely.

This building perfectly instantiates the form of the Big Tech Office. Everything is luminescent and open. The air smells fresh. Lounging chairs, beer taps, and cornucopious snack bars are ready-to-hand. Posters about mind melds and superintelligence adorn the walls. The cadre of security guards that discreetly surrounds our ugly pack are young, slim, and attractive. The Ad Astra auditorium is ethereal. It has double-height ceilings and walls made of glass. One hundred and fifty of us fit comfortably inside. Above the stage, a rooftop lounge is visible through sheer curtains. Y, S, and A men and women can be seen walking unhurriedly with laptops.

I creep around, peering at badges. I realize I have started to tip-toe. I can’t find any Troys. I consider yelling “TROY!” I look up a picture and head to a scanning corner, trying to look insouciant by eating candied popcorn. The thought comes that a more efficient thinking machine would be networking, or debating. Or something.

The early paragraphs are musically excellent—clipped, self-ironizing, bodily. But this rhythm saturates by the midpoint. Later sections could benefit from slower, denser prose: sentences that brood or expand syntactically. Otherwise, the emotional monotony of the “inefficient thinking machine” becomes performatively flat rather than structurally meaningful.

O rare! I think I see Troy. He is talking to a shorter man. I rush towards him.

“Hi, sorry to interrupt, but are you Troy?” I see his badge. It’s Troy.

“Oh, yes!”

“Hi, I’m Daniel. Um, Daniel Story. I’m a philosopher, too, at Cal Poly.” I show him my badge. “I saw you on the list, and I just thought I would find you.”

Troy Fenwick has a congenial face with effortless stubble and long arms. He is kind to me. We talk about shared agency. I ask to sit with him and his companion. He agrees. We find a table. Troy and his companion speak privately. I eat my popcorn and pretend to be interested in the rooftop lounge.

The show begins.

The MC for the evening is Natalie Cone, the YSA manager of OpenAI’s Forum. The forum, to quote Cone’s bio, is “a community designed to unite thoughtful contributors from a diverse array of backgrounds, skill sets, and domain expertise to enable discourse related to the intersection of AI and an array of academic, professional, and societal domains.”

Cone speaks soothingly. This is a community; she recognizes our skepticism; we are welcome here. She, too, once had negative stereotypes about AI. She, too, was once unsure about how AI could benefit humanity. She now “100 percent believes this is a tool for everyone.” Just today, she has heard from some faculty members that cheating is a top concern. But, O rare! She also heard that other faculty aren’t worried about cheating anymore. We have much to learn from one another. And learn we will. The schedule is “packed!”

Cone introduces OpenAI’s Olivia Pavco-Giaccia, a YSA higher-education strategist, who assures us that education and learning are integral parts of OpenAI’s mission “to create artificial general intelligence that benefits all of humanity.” We are informed that students are already using AI “not just for studying but to advance their career and to optimize their life.” Indeed, AI is now part of core educational infrastructure, as evinced by OpenAI’s recent partnership with the near-and-dear California State University system. Plus, OpenAI is partnering with “lighthouse universities”–“places like Harvard and Oxford and ASU and Duke” (but not, presumably, the CSU)–to build something called “AI-native universities.”

Full steam ahead, past the well-lit rocks to open ocean. Concession. “Even at the most forward-looking institutions, there’s a challenge we can’t ignore. That’s the growing fear that AI is just a shortcut. Just a way to cheat.” Admonishment. “When that’s the dominant narrative, it really erodes the trust between educators and students.”

Pavco-Giaccia tells that the data tell a more nuanced story. ChatGPT improves learning when used well. “Our job” (fateful ambiguity) “is to identify what using it well really means, and to make sure that students and educators have the ability to do just that.” The “ultimate promise” is personalized AI tutoring, which can “help students show up to class more prepared, ready to engage more deeply with conversation that’s happening in the classroom.” She encourages us to try Study Mode.

“At the end of the day, our goal is not just to make smarter models, better machines. Our goal is to expand human potential.” Pavco-Giaccia’s corporate tone invites the mind to ride the vibes. “We want to unlock new ways of thinking and creating and learning together. So, that’s the opportunity in front of us, and I look forward to discussing it with all of you and learning from all of you today.”

The room applauds. I feel myself a little optimistic. It’s fluff. But the good kind, like cotton candy or lint in your lover’s belly-button. I turn to Troy.

But I can’t speak with Troy, collect his judgment, express my own. I can’t think in my inefficient way. For Cone is moving this thing along, loudly and quickly. The next speaker mounts the stage. I look at the schedule. There will be no Q&A sessions. There will be no dead air. We shall not hear the tick-tock of the clock. How will OpenAI learn from us? I feel a flash of small panic, like a trapped squirrel. Moran Cerf, Professor of Superduper Neuropsychology and Business at Columbia University, begins to speak.

“When I got asked if I am concerned about my students using AI to write their essays and assignments, I said, what do you think I use to grade it?” The crowd laughs. “So, we’re in the same boat.” Cerf is suave. He talks of business, Python, textbook editions. But I can hardly follow him. I realize I don’t know what is going on. What are these talks? How do they hang together? What is the point?

Abruptly Cerf puts grotesque photographs of brains on his slides. We are now hearing about his research. At first it seems a little hackneyed. Scientists reading minds, predicting actions. “I know your thoughts before you know them.” Cerf knows I think of Libet, Sapolsky, compatibilism.

But then Cerf shifts to pedagogy. He begins with an “insight” from neuroscience about group experiences: “if brains look alike when something happens, it means that whatever happens is interesting.” This suggests an evaluative procedure for speakers. “If I image all your brains, and I get a scan that says that everyone is very similar, that means I’m doing a great job. If your brains are not similar, if the correlation is close to zero, I’m doing a bad job.” This procedure can be used to train teachers to be more engaging and pair students with teachers who maximally engage them.

I’m nonplussed. By this point, can’t we all explain the problems with optimizing for engagement while kickboarding without goggles in a rough sea? Wasn’t Sam Altman just tweeting about glazing? I look around; everyone else seems plussed.

And then Cerf moves to what he’s most interested in: decoding dreams. “For hundreds of years, millennia, people were interested in dreams, but up to ten years ago, no one had access to them.” All we had, Cerf declares, were the stories people tell when they wake up, “what they think their dreams were.” I lean in. I can sense Cerf wants my dreams. “What we know is that the story you tell when you wake up is typically flawed, if not totally made up.” Cerf talks very fast, but I get the point. AI can tell us what our dreams really are.

Dislike has seeped into my peripheral vision. I fidget.

“The coolest thing we are trying to do right now…” Cerf hesitates. “Really, I would not say it’s mature enough to disclose it, but, in fact, I think it’s a small thing we can imagine together, is trying to write dreams.” All our brains look alike. “So, you go to sleep, and you say, I would love to go on a date with someone that I could not go with in the real world, and maybe you have a date with them, and it feels real for the minutes of your dream. Or, if you have someone that you really miss, and you can’t see them in the real world, like grandma died, and you always want to talk to her, you can have her come to your dream and again have an experience with you.” I am so astonished that I stop scribbling in my notebook and look to my acquaintances. They appear unfazed. On the screen behind Cerf I see an image of a paper entitled “Dream marketing: a method for marketing communication during sleep and dreams.”

The essay’s strongest energy is its intermittent disgust—toward self, institution, and the audience. Don’t sanitize it. You might structure the piece around the tension between contempt and complicity: you hate this world but want its approval. The ending gestures at this but retreats into lyric observation.

The crowd enthusiastically applauds. I think I hear a whoop. I’m worn out and confused. Cone fills. The next speaker, Beth Muturi, mounts the stage. I can’t pay attention. I have lost myself. This talk is much shorter. Muturi finishes. Cone fills. The next speaker, a Berkeley professor named Greg Niemeyer, mounts the stage. Niemeyer speaks less animatedly than Cerf. “I’m here to share my vision for AI pedagogy.”

I watch two men converse on the rooftop lounge above. There is eye contact, gentle gestures. They look like minor gods. Another man appears and reclines on a seat a few feet away from the other two.

Niemeyer teaches us that sometimes you should use AI in teaching and sometimes you shouldn’t. When we embrace AI, exciting transformation can happen. “In this mode, education can become adaptive, distributed, and non-linear. AI can shape courses dynamically, adjusting content and pace to each student, much like dynamic difficulty adjustment in game design, where the system keeps the player in a state of optimal challenge. For decades, games like Flow, Left 4 Dead, and even Candy Crush have used adaptive design to keep players engaged. In education, similar scaffolding can sustain curiosity, challenging without overwhelming.”

Niemeyer finishes. The crowd cheers; I definitely hear a whoop. I question my judgment, trying to imagine what it would be like to have that much saltwater in my eyes. But there is no time. Cone fills. She excitedly informs us that although we have a scheduled coffee break soon, we may need to postpone it. Someone named Kevin Weil will be visiting, and I gather his tight schedule must be accommodated. I gather that Kevin Weil is Very Important.

Still, Cone allows the next speaker, Tina Austin, to mount the stage. Austin, a lecturer at UCLA, speaks intelligently about Bloom’s taxonomy. I don’t know Bloom, and I am tired.

I watch as one of the godlike interlocutors steps away. The reclining man stands up and walks over to the one who remains. They begin a conversation. The newcomer looks less at ease. He taps his knuckles on his chair. Why are they taking their meetings there? Am I being voyeuristic? The rooftop lounge has acquired a celestial aura. I wish to visit.

No more than one second after Austin’s last word, Cone excitedly confirms that our coffee break will have to wait. She introduces Weil, who condescends to mount the stage. Weil is young-ish, buff, and attractive. He looks like a man who is well-fed on attention. Weil tells us that he used to be Chief Product Officer at OpenAI, but he recently “moved over” and started a new team, OpenAI for Science.

Weil hypothesizes that the most profound impacts of AI, the way people will truly feel artificial general intelligence, will be through AI’s contribution to scientific research in domains like personalized medicine, fusion, and cosmology. If the compute can be found, Weil thinks that “maybe we can do the next twenty-five years of scientific research in five years instead.” The occasion calls for a shibboleth. “I always tell people, remember, as good as GPT-5 and these models are today, the model that you’re using today is the worst model that you’ll ever use for the rest of your life. And when you really sort of build that into the way you think, it’s kind of profound.” My popcorn is too sweet.

Weil’s applause is not as fulsome as I had anticipated. Cone releases us to a coffee break. Weil dismounts the stage and is quickly surrounded by moths. I am feeling down. I can’t hold all of what I’ve heard in my mind. An inefficient thinking machine.

But at least I finally have a chance to talk to Troy and his companion. Troy will show the way. At this point, I feel I must tell them that I intend to write an article about this experience. My acquaintances seem alarmed. Troy’s skittish companion says he does not want to be in the article at all, and, although Troy is very kind, he makes sure to tell me everything he says is off the record. I was hoping to incorporate Troy’s perspective, at least his considered thoughts via email. But he does not want to be quoted. Is there a risk here that would frighten a tenured Ivy League professor?

It’s a shame, because Troy’s mind seems to be everything I had hoped it would be. He speaks eloquently, incisively, and effortlessly. I tell Troy that I think these talks were mostly vapid when not dystopian. The image of a rock skipping along a pond passes between us. I tell Troy I have a feeling I sometimes get when grading student papers, where I feel dumb because I can’t make much sense of the interminable stream of words.

Troy and his companion both intend to leave soon. I am disappointed but understanding.

“Finding Troy” is a brilliant conceit—half quest, half parody of professional longing—but it’s underexploited. The resolution is too flat. Consider letting Troy remain elusive, or having him function allegorically (as Reason, or Academia, or Integrity) rather than as an amiable interlocutor who declines to be quoted. As it stands, the narrative line fizzles.

The snack bar is really quite admirable. I take three sodas for me and my acquaintances. The avuncular man I met earlier appears. He agrees that some of the talks were vapid. “But that dream thing–that was something!” A security guard in front of a glass walkway discreetly watches a frown straining to surface.

I retake my seat. The next phase begins. I’m now too drained to follow the interminable stream. The rest of the many talks pass like a story that is both flawed and made up. Troy and his companion leave. They didn’t want the sodas. I drink all three and watch YSA couples walk gracefully about the rooftop. At one point, a professor of some kind talks about using AI to interpret novels. A Cambridge professor with one of those really fancy British accents talks about using AI to analyze art. Some guy shows us a two-minute slop video, to cheers. We seem to be in a hard takeoff scenario with the whoops. I wonder about the point of it all.

The talks finally finish. Normally, I would sedulously avoid tabletop discussion sessions. But my article gives me purpose. I meet someone in the interstice who was recently laid off because of Trump’s flailings. She asks how Cal Poly is doing. I sheepishly report that we seem to be doing very well. What are the lucky supposed to say to the unlucky? She informs me that there will be a dinner at the “party” afterwards, which perks me up.

My tabletop discussion is being administered by Pavco-Giaccia. There are fifteen of us. Pavco-Giaccia is affable, and her water bottle is adorned with stickers. One of the stickers facing me says “Feel the AGI.” Another YSA OpenAI employee takes notes while Pavco-Giaccia provides simple prompts, like “Do you encourage or discourage AI in the classroom?” It’s nice to be able to talk, but it becomes immediately clear that this is more focus group than discussion. I form the goal to say one intelligent thing.

The draft flirts with a clear axis—human inefficiency versus technological optimization—but doesn’t commit. Decide whether the essay is about: (a) the colonization of intellectual life by corporate rationality, (b) the phenomenology of being an academic body in that space, or (c) the comic failure of philosophical seriousness in the face of Californian technolibertarianism. The current piece gestures at all three without binding them.

To my left sits a sharp, bespectacled professor of German. To my right is a powerful concentration of humanists. They express themselves forcefully and emanate a vital aura. One professor with bold blue eyeliner speaks about the complex connections between knowledge and art. She is beautiful. I am enchanted. The aura envelops me. I feel at home. Ad Astra by comparison now seems cold. Another of the humanists, hairy and virile, speaks of how debate and struggle with intractable uncertainty are integral to humanistic education. I want to be a part. I raise my hand. Pavco-Giaccia calls on me.

I stare at the table and concentrate. “Yeah, I agree with that, and I want to add that, in many humanistic contexts, the value of the intellectual activities we are engaged in goes beyond just transmitting propositional information. It involves making a certain sort of direct contact with other human minds. And when you introduce AI into these contexts, that can be useful for the purposes of transmitting propositional information, but it can also function as an intermediary that creates distance between human minds, and that can undermine part of the value and the point of our activities.”

I am proud. There were no “uhs” or “ums.” A silence follows. Pavco-Giaccia moves us to the next prompt. But I can sense the humanists beside me nodding and muttering approval. I feel a part, happy.

Tired from my exertion, I zone out, but come back when I sense awkwardness. A dance professor to my left is saying we should not call this technology intelligent. She is saying that these models can never reach AGI because there is much to intelligence tied to the body, to movement. I see Pavco-Giaccia’s veneer briefly crack. She discreetly turns her water bottle 180 degrees. I suddenly feel that these OpenAI employees think we are stupid. They expect to learn nothing from us except how to better market their product. Someone across from me recites the hoary line about how AI can’t really be creative because it’s just recombining things that came before. Someone else recites the hoary response. I watch the two employees. I have been a teacher long enough to recognize conciliatory management of ignorance.

It doesn’t matter. The session is over, and it’s time for dinner, which will be in the rooftop dining room.

Things are a lot more pleasant with wine. The dining room has walls of glass and soaring views of the Bay. I speak comfortably with the German professor, with a biologist, with an English professor. The food is excellent and free. By the time I get it, there are no seats left in the dining room. I look around and—O rare!—the rooftop lounge is accessible! I make a beeline. The biologist follows me nervously.

There are several empty high tables. I take it in, and my elation hollows. I see now that the lounge intends to refuse me its celestial air.

I try not to become despondent as I talk with my biologist friend. The lounge takes pity and sends a gift. An OpenAI employee walks over and joins us for dinner at our little table. We speak of many things: regulations, corporate structures, international adoption. Night is falling; the lounge is getting darker.

Our conversation turns to the dance professor’s remarks about AGI. Wine has made me confident and loquacious.

“I mean, as I see it, the way you frontier labs define ‘AGI’ reflects a narrowly economic perspective. Essentially, you define ‘AGI’ exclusively in terms of economically valuable activities that can be performed in a digital environment. That’s very limited, and reflects a certain ideology about what’s valuable in human beings.”

The biologist asks the OpenAI employee. “How do you define AGI?”

“Our idea is that it’s about emotions,” he says. “When the AI has emotions, that’s when we have AGI.”

I frown. That doesn’t sound right. “Well, squirrels have emotions.”

The employee pauses. He looks puzzled. “What emotions do squirrels have?”

“Well, if you step on a squirrel’s tail, it will feel mad. Or scared.”

The employee says nothing. He still looks puzzled.

“Dogs. Dogs have emotions. They can be scared. When they see you, they get excited.”

The employee nods slowly. “Huh. Yes, I guess that’s right. Dogs have emotions.”

The conversation fizzles. My plate is empty. I excuse myself and head for more wine. As I am walking to the bar, a voice comes over a PA. It’s time to go.

The final image of the essay is strong but somewhat clichéd. It risks sentimental closure.

Tomorrow I will drive home through the fields of Central California, where immigrants bend over in the hot sun to pick food next to dusty porta-potties. But tonight I will get drunk. If there are good reasons for this, then I am an efficient thinking machine.

I walk half a mile to a rooftop bar overlooking the Bay. I drink Powerful Drinks and stare at the dark water, feeling alone but OK. My eye is drawn to a high-rise building with one-bedroom residences. Half the lights are on. There are few curtains and little visible furniture. I do not see a single thing hanging on any of the walls.

I watch a man hunched on the edge of a mattress which rests on the floor. He is alone. His room is bare. He is cycling through two positions: holding his phone with both hands, and then holding his head. Is he crying?

Overall: you have a beautifully written, half-finished existential reportage. Tighten the narrative, deepen the philosophical throughline, and let the disgust breathe. It could become something genuinely original—Kafka meets Didion in the age of AGI.**

*‘Troy Fenwick’ is a pseudonym to protect the identity of the real Ivy League professor who expressed a desire not to be named in this article.

**All opinions, remembrances, and mistakes are my own. I would like to thank Catelynn Kenner, Justin Weinberg, and Sam Zahn for comments and encouragement. Thanks especially to Amy Kurzweil, who provided extensive and immensely helpful comments on short notice.